When talking about the reforms that the revolution brought to Russia, they mention education, medicine, and, of course, religion. There is certainly talk about calendar reform. Indeed, in January 1918, Russia switched to the Gregorian calendar, catching up with most European countries. This had an obvious and clear meaning - firstly, the Julian calendar was inaccurate, and secondly, the most advanced state on earth could not be 13 days behind the rest of the world.

However, it is less known that the calendar reforms did not end there. They occurred, however, not in the turbulent years of the first years of the revolution, when all the traditions of the old world were being destroyed, but in the relatively stable year of 1929.

At the end of August 1929, a decree of the Council of People's Commissars of the USSR “On the transition to continuous production in enterprises and institutions of the USSR” was issued. Within the framework of this idea, it is created new calendar. The year is divided into 72 weeks of five days each. Another five days remain for public holidays, which are not included in any weeks. This system was first published in the newspaper “For Industrialization” on March 18, 1930, as part of a resolution of a special government commission under the Council of Labor and Defense. The essence of this idea was that employees of an enterprise or institution were divided into five groups (they were assigned colors, five in total), each of which had its own day off.

The idea, however, took root with difficulty. Let us remember, by the way, “The Golden Calf” by Ilf and Petrov:

“When the methodological and pedagogical sector switched to a continuous week and, instead of pure Sunday, Khvorobyov’s days of rest became some purple fifths, he disgustedly spent his pension and settled far outside the city.”

The text was written just between 1929 and 1931.

On November 21, 1931, a new decree of the Council of People's Commissars of the USSR was issued - “On a continuous production week in institutions.” Despite the name, the resolution specifically allows “intermittent” working week of six days. Five working days now became mandatory for everyone, but the sixth - the 6th, 12th, 18th, 24th and 30th of each month, respectively - was declared a day off (in the case of February it was postponed to March 1st). “Those who didn’t fit in” also became workers on the 31st.

It is interesting that the days of this six-day week in many calendars did not have names - only a number.

This calendar worked, and worked for quite a long time - until the summer of 1940. Elena Bulgakova mentions this in her diaries - due to the passport office not working on the 18th, Bulgakov has problems obtaining documents for traveling abroad. References to it are also found in “Youth Restored” by Zoshchenko:

“In any case, he now regularly visits Children’s once every six days, and Lida’s happiness is beyond description.”

The six-day period appears in the credits of Volga-Volga.

This system was introduced in institutions and enterprises, excluding those that must work seven days a week - public canteens, transport, etc.

However, it, of course, remained a purely urban phenomenon. There was never a clear work schedule in the village, so any reforms to the working week or day essentially went unnoticed there. Bolshevik innovations did not in any way affect people who still lived according to the religious calendar.

Of course, both the five-day and six-day weeks were largely directed against the church and religiosity in general. They completely excluded Sundays and struck at the traditions of Muslims and Jews. The religious calendar (no matter from the Nativity of Christ or from the Hegira) could not coincide with the new one. In this sense, the calendar reform of 1929-31 can be considered as bringing the revolutionary impulses of the 20s to the absolute. By 1929, the new ideology had burst into all spheres of traditional life - the names of saints were replaced by the names of martyrs of the revolution or completely unprecedented designs, it was questioned official marriage, religion was abolished, changed geographical names. The last stage Such changes became the reform of time itself.

Two more points can be considered as minor elements of the new calendar system. The first is the counting of dates from the October Revolution, which was extremely common on the calendars of those years, but of course combined with the traditional counting from the beginning of our era.

The Bolsheviks, however, were not innovators in the idea of changing the calendar. Julius Caesar and Peter the Great were partly guided by the same ideas, and the French had exactly the same motives during their Great Revolution. In France, we recall that the new calendar lasted 13 years, from 1793 to 1806, until Napoleon abolished it - revolutionary ideas did not fit into the new imperial concept.

Our revolutionary calendar did not fit into it - already on Soviet soil.

June 26, 1940, when the decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR “On the transition to an eight-hour working day, to a seven-day working week and the prohibition of the unauthorized departure of workers and employees from enterprises and institutions” was adopted. It is mainly devoted to issues labor legislation, but in short second paragraph states: “Transfer to all government, cooperative and public enterprises and institutions work from a six-day week to a seven-day week, considering the seventh day of the week - Sunday - as a day of rest.” This is how an entire era of Soviet life ends casually and imperceptibly.

Why is this happening? Of course, economic feasibility also played a role, but I think it was not the only one. The very concept of USSR policy, both internal and external, is changing. From the only communist, revolutionary country in a ring of enemies, the Soviet Union is transformed by the will of Stalin into a great but ordinary power, a kind of empire. This empire is already participating in world politics, concluding pacts with European powers (and not only about peace, as in Brest-Litovsk 1918, but also about mutual assistance and allied actions), and participating in European wars. In such a country, a “normal” calendar is needed. This return of the seven-day period and the word “Sunday” into everyday use is one of the bells of that new policy, which will continue with the resolution of the activities of the Russian Orthodox Church and the restoration of shoulder straps in 1943 and a toast “to the health of the Russian people”, the transformation of the People's Commissariats into ministries and much more. In a word, it was an unconditional departure from revolutionary politics and aesthetics to the politics and aesthetics of the Soviet Empire.

Konstantin Mikhailov

with the abolition of the seven-day week and Sunday. Revolutionary calendar - the Bolsheviks' struggle with Christian week

-  -

-

-  -

-

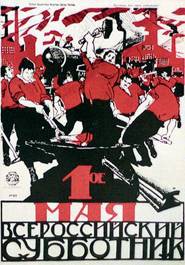

The Soviet revolutionary calendar with a five-day week was introduced on October 1, 1929. Its main goal was to destroy the Christian seven-day weekly cycle, making Sundays working days. However, despite the fact that there were more days off (6 per month instead of 4-5), such an artificial rhythm of life turned out to be unsustainable, it contradicted both everyday habits and all established folk culture. Therefore, the revolutionary calendar, under the pressure of life, gradually changed towards the traditional one, which was restored in 1940. This calendar reform took place as follows.

26 August 1929 Council People's Commissars The USSR, in its decree “On the transition to continuous production in enterprises and institutions of the USSR,” recognized it as necessary, starting from the 1929-1930 business year (from October 1), to begin a systematic and consistent transfer of enterprises and institutions to continuous production. The transition to “continuous work”, which began in the fall of 1929, was consolidated in the spring of 1930 by a resolution of a special government commission under the Council of Labor and Defense, which introduced a unified production timesheet-calendar.

-  -

-

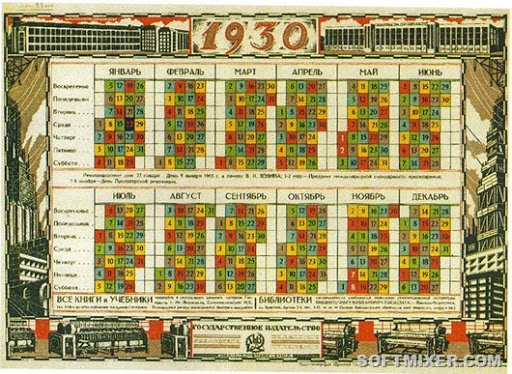

IN calendar year 360 days were provided, and accordingly 72 five-day periods. Each of the 12 months consisted of exactly 30 days, including February. The remaining 5 or 6 days (in a leap year) were declared “monthless holidays” and were not included in any month or week, but had proper names:

– Lenin Day, which followed January 22.

– Labor Days (two) following April 30th.

– Industrial days (two) following November 7th.

– In leap years, an additional leap day followed February 30.

A week in the USSR in 1929–1930. consisted of 5 days, while they were divided into five groups named by color (yellow, pink, red, purple, green), and each group had its own day off per week.

The five-day period took root with exceptional difficulty - in fact, it was a constant violation of the usual biological rhythm of people’s lives. Therefore, the Bolsheviks decided to retreat slightly.

By the Decree of the Council of People's Commissars of the USSR of November 21, 1931 "On the interrupted production week in institutions", from December 1, 1931, the five-day week was replaced by a six-day week with a fixed day of rest falling on the 6th, 12th, 18th, 24th and 30th of each month ( March 1 was used instead of February 30, each 31st was considered an additional working day). Traces of this are visible, for example, in the credits of the film “Volga-Volga” (“the first day of the six-day week”, “the second day of the six-day week”...).

-  -

-

Example of a calendar page using a six-day calendar

Since 1931, the number of days in a month has been returned to its previous form. But these concessions did not change the main goal of the calendar reform: the eradication of Sunday. And they also could not normalize the rhythm of life. Therefore, with the first signs of rehabilitation of Russian patriotism on the eve of the war, Stalin also decided to stop the fight against traditional structure calculation of time.

The return to the 7-day week occurred on June 26, 1940 in accordance with the decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR “On the transition to an eight-hour working day, to a seven-day working week and on the prohibition of unauthorized departure of workers and employees from enterprises and institutions.” However, the week in the USSR began on Sunday, only in more later years- from Monday.

Despite the fact that chronology continued according to the Gregorian calendar, in some cases the date was indicated as “NN year of the socialist revolution,” with a starting point of November 7, 1917. The phrase “NN year of the socialist revolution” was present in tear-off and flip calendars up to and including 1991 – until the end of the Communist Party’s power.

Categories:

Which of the readers heard from their ancestors (and did not read in a book) that until 1940 there was a six-day working day with fixed days of rest falling on different days seven day week? Not many people who. But in 1940 everyone knew this. This article is about something that everyone has forgotten: the regulation of working time in the USSR...

Under the damned tsarism

The tsarist regulation of working time applied, with some exceptions, only to industrial workers (and then so-called qualified ones, that is, with the exception of the smallest enterprises) and miners.

The working day was limited to 11.5 hours, a standard seven-day working week was assumed with one day of rest on Sunday, while before Sundays and holidays a 10-hour working day was provided (the so-called eve days).

There were 13 holidays falling on any day of the week, in addition, 4 more holidays always fell on weekdays. Paid leave was not provided. Thus, in an average non-leap year there were 52.14 Sundays, 4 holidays that always fell on weekdays, and another 11.14 holidays that did not fall on Sunday, for a total of 297.7 working days in the year.

Of these, 52.14 were Saturdays, and another 7.42 were created by mobile holidays that did not stick to Sunday. In total, 59.6 working days were short, and 238.1 were long, which gives us 3334 standard working hours per year.

In fact, no one in industry agreed to work so much anymore, and the factory owners understood that people would work more efficiently if they were given more time to rest.

On average, at the beginning of the First World War, factories worked 275–279 days a year, 10–10.5 hours (different studies gave different results), which gives us approximately 2750 — 2930 hours per year.

Provisional government. Early Soviet power: war communism and NEP

Since May 1917, the Provisional Government fell into the hands of the socialists, who had been promising the working people an eight-hour shift for decades. The Socialists did not change their course, that is, they continued to promise an eight-hour meeting in an uncertain future, which (for the Provisional Government and the Socialist Revolutionaries) never came.

All this mattered little, because the industry was collapsing, and the workers became insolent and did not listen to their superiors; by the end of the summer of 1917, in fact, no one worked more than 5–6 hours a day (well, the output was the same as if they worked 3–4 hours).

Already on October 29, 1917, the Bolsheviks fulfilled one of the main points of their pre-revolutionary program - by a special decree they proclaimed an eight-hour working day, that is, it turned out to be a seven-day week with one day off and an eight-hour working day. The Labor Code of 1918 further expanded these provisions.

A month's paid leave was introduced; and between the end of the working day on Saturday and the beginning on Monday there should have been 42 hours, which, with one-shift work with a lunch break, gave a five-hour working day on Saturday; Before the holidays, the working day was reduced to 6 hours.

The number of holidays was reduced to 6, all on a fixed date, these were familiar to us New Year, May 1 (day of the International) and November 7 (day of the Proletarian Revolution) and completely unfamiliar ones: January 22 (day of January 9, 1905 (sic!)), March 12 (day of the overthrow of the autocracy), March 18 (day of the Paris Commune).

Using the calculation method shown above, in an average year, taking into account vacations and shortened days, there were 2112 hours, 37% less than according to the Tsarist Charter on Industry, 25% less than they actually worked in Tsarist Russia. This was a big breakthrough, if not for one unpleasant circumstance: the real industry did not work at all, workers fled from the cities and died of hunger. Against the backdrop of such events, anything could be written in the law, just to please the supporting class a little.

Since the people of that era were still strongly committed to religious holidays, but it was unpleasant for the Bolsheviks to mention this in the law, they were renamed special days recreation, of which there were supposed to be 6 per year. The days were assigned to any dates at the discretion of local authorities; if these days turned out to be religious holidays (which invariably happened in reality), then they were not paid; therefore, we do not include additional holidays in our calculations.

In 1922, industry began to slowly revive, and the Bolsheviks slowly came to their senses. According to the Labor Code of 1922, vacation was reduced to 14 days; If the vacation included holidays, it was not extended. This increased the annual working hours to 2,212 hours per year.

With these norms, quite humane for the era, the country lived through the entire NEP.

In 1927–28, May 1 and November 7 received a second additional day off, reducing the work year to 2,198 hours.

By the way, the Bolsheviks did not stop there and promised the people more. Solemn anniversary "Manifesto to all workers, toiling peasants, Red Army soldiers of the USSR, to the proletarians of all countries and the oppressed peoples of the world" 1927 promised an early transition to a seven-hour working day without reducing wages.

The Great Break and the first five-year plans

In 1929, the Bolsheviks, against the backdrop of the Great Revolution, were seized by a passion for exotic experiments in the sphere of regulation of working time. In the 1929/30 business year, the country began to vigorously transfer to a continuous working week with one floating day off per five-day week and a seven-hour working day (NPD).

It was the strangest timetable reform imaginable. The connection between the seven-day week and the work schedule was completely interrupted. The year was divided into 72 five-day days and 5 permanent holidays (January 22, now called V.I. Lenin Day and January 9, two-day May 1, two-day November 7).

The day of the overthrow of the autocracy and the day of the Paris Commune were canceled and forgotten by the people forever. New Year became a working day, but remained in people's memory. Additional unpaid religious holidays were also permanently abolished.

Not a single day in the five-day week was a general day off; workers were divided into five groups, for each of which one of the five days was a day off in turn. The working day became seven-hour (this was promised earlier, but no one expected that the seven-hour clock would come along with such confusion).

The vacation was recorded as 12 working days, that is, the duration remained the same. The minimum duration of Sunday rest was reduced to 39 hours, i.e. eve days disappeared during single-shift work. All this led to the fact that there were now 276 7-hour working days in the year, giving 1932 working hours per year.

Soviet calendar for 1930. Different days are highlighted in color five day week, however, the traditional seven-day weeks and the number of days in months remained.

The five-day workday was hated both among the people and in production. If spouses had a day of rest on different days of the five-day week, they could not meet each other on the day off.

In factories, which were accustomed to assigning equipment to certain workers and teams, there were now 5 workers per 4 machines. On the one hand, the efficiency of equipment use theoretically increased, but in practice there was also a loss of responsibility. All this led to the fact that the five-day period did not last long.

Since 1931, the country began to move to a six-day working week with five fixed days of rest per month and a seven-hour working day. The connection between the working week and the seven-day period was still lost. In each month, the 6th, 12th, 18th, 24th and 30th were designated as days off (which means that some weeks were actually seven-day). The only holidays left were January 22, the two-day May Day and the two-day November.

With a six-day workday, there were 288 working days of 7 hours a year, which gave 2016 working hours. The Bolsheviks admitted that the working day had been increased, but vowed to increase wages proportionately (by 4.3%); in practice this did not matter, since prices and wages rose very quickly in that era.

The six-day system was able to somewhat reduce the damned confusion with the timesheet and calendar and more or less (in fact, about half of the workers were transferred to it) took root. Thus, with a rather short nominal working day, the country lived through the first five-year period.

We must, of course, understand that in reality the picture was not so joyful - the storming typical of the era was ensured through continuous and lengthy overtime work, which gradually became the norm from being an unpleasant exception.

Mature Stalinism

In 1940, the era of relatively liberal labor rights came to an end. The USSR was preparing to conquer Europe. Criminal penalties for being late, a ban on dismissal for at will- of course, these measures would look strange without the accompanying increase in workload.

June 26, 1940 transition to a seven-day work week. This call to all workers of the USSR was made at the IX Plenum of the All-Union Central Council of Trade Unions. In addition to the seven-day workday, during the plenum it was also proposed to introduce an eight-hour working day.

Since 1940, a seven-day week with one day off and an eight-hour working day was introduced. Holidays became 6, the day of the Stalin Constitution, December 5, was added to the old holidays. The shortened pre-holiday days that accompanied the seven-day week until 1929 did not appear.

Now there are 2,366 working hours in a year, as much as 17% more than before. Unlike previous eras, the authorities did not apologize to the people about this and did not promise anything. With this simple and understandable calendar, which gave a historical maximum (for the USSR) of working time, the country lived until the complete collapse of Stalinism in 1956.

In 1947, amid a general return to national tradition, the holiday of January 22 was replaced by New Year.

Khrushchev and Brezhnev eras

In 1956, Khrushchev, having overcome the resistance of the elites, opened new page— labor law has sharply softened again. Since 1956, the country has moved to a seven-day working week with one day off and a seven-hour working day; in practice, the transition took 3–4 years, but it was complete.

In addition to the seven-day period, the country received a new relaxation - all pre-weekend and pre-holiday days were shortened by two hours. The holidays remain the same. This led to a sharp reduction in working hours; there were now 1,963 working hours per year, a 17% decrease. In 1966, the familiar March 8 and May 9 were added to the holidays, which reduced the working year to 1950 hours, that is, almost to the times of the half-forgotten five-day week.

And finally, in 1967, already under Brezhnev, the most fundamental of the reforms took place, which gave the form of the work schedule familiar to all of us today: a seven-day work week with two days off and an eight-hour working day was introduced.

Although the workweek had 5 working days of 8 hours, its duration was 41 hours. This extra hour took shape and formed 6-7 black (that is, working) Saturdays hated by the people over the course of a year; on which exact days they fell was decided by the departments and local authorities.

The length of the working year increased slightly and now amounted to 2008 hours. But people still liked the reform; two days off were much better than one.

In 1971, a new Labor Code was adopted, which contained one pleasant innovation: vacation was increased to 15 working days. There were now 1,968 working hours per year. With this labor law Soviet Union and reached its collapse.

For reference: today, thanks to the reduction of the working week to 40 hours, the increase in vacation to 20 working days, and holidays to 14 days, which always fall on non-weekends, we work 1819 hours in an average non-leap year.

link